Zen, thinking and the (sub)conscious

This second lesson we are going to talk about how and why meditation works. We do this by looking at our brains and the interaction with the rest of our body.

Every person has on average about 60,000 thoughts a day. More than 90% of this is the same as yesterday. Most of it also runs on autopilot.

That we generate a lot of thoughts is not so much the problem. But the fact that these thoughts dominate us, especially if some of those thoughts are undesirable, is the real issue. To be aware of that and to do something about it, a training is needed. A training of the mind. And meditation is primarily a training of the mind.

Now we have a phenomenal ability that virtually no other living thing possesses: we can choose to think of something else. And the special thing is that it does not matter whether what we think NOW is already a reality. We can bring something to life in our minds alone.

Meditation is therefore ideally suited.

How does this work?

It is important that we become aware of the fact that we are thinking and that our thoughts are running an automatic process. This is what we practice. Every time we notice that we have been distracted by a story in our head, we return to follow our breathe. It is very important to make this ‘cut’.

What we do when we make that ‘cut’ is that in our brains we disassemble the nerve cells (neurons) involved in these thoughts. The network of these neurons is becoming weaker. We use this exercise to loosen the neural connections in certain networks.

This type of thought then becomes less in the course of time.

Within the Zen tradition, we place a lot of emphasis on letting go of the old and strengthening your intuition by allowing the silence and the space between thoughts to come up with the solution in a natural way and time.

How does it work in your brain?

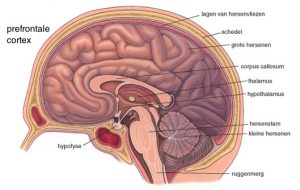

At the front right side of your head you take the decision to start meditating and focus your attention to your breathing. This area is called the prefrontal cortex and is the most recent part of the human brain.The rest of the big brains are then quieting down, the thoughts are subsiding a bit.

At the front right side of your head you take the decision to start meditating and focus your attention to your breathing. This area is called the prefrontal cortex and is the most recent part of the human brain.The rest of the big brains are then quieting down, the thoughts are subsiding a bit.

Signals are being sent to our limbic system: the part of our brain in the middle where the thalamus and hypofyse are located. This part is regulating our emotions. Chemical processes and the producing of hormones is mostly done here. Because other parts of our brain are working less hard, this limbic system can begin to process our emotions on a subconscious level.

The hormones saying: “it has settled down, I feel good” are spreading to the rest of our body through our blood. The rest of the body signals back to our little brain (reptile brain) that it is okay and then that part is responding by letting our heart beat slower, our respiration is slowing down etc.

The reason why many people continue to meditatie, is because of the processing of our emotions in the limbic system. After a few weeks of meditation you can begin to notice how certain thoughts and situations are no longer troubling you (that much) and that you can put everything in a broader perspective.

Kinhin – walking meditation

Within a number of zen schools, meditative walking, chinhin, is just as important as meditative sitting, zazen. Kinhin is considered a form of “zen in action”. Kinhin is used in almost all zen schools to alternate the periods of sitting (physical inactivity) with physical activity. By walking the blood flow is promoted again and possibly some stiff knee joints are made flexible again.

Kin means: which is vertical, which directly connects two opposite directions, such as heaven and earth. Hin means: go.

You are the ongoing connection between heaven and earth. Kinhin requires much greater effort than zazen in terms of attention and intensity, even though it seems to be more relaxing physically. There is much more distraction and reason to judge.

There are different forms in which kinhin takes place. In most Zen monasteries, the master, followed by his students, walks a few laps in the meditation room. Sometimes outside walks are made.

The most common methods of kinhin are the slow and fast form.

Slow kinhin

With the posture of the upper body, it is important, as with sitting meditations in Zen, to again pay particular attention to a straight back. The elbows are slightly forward such that the forearms form a straight line from elbow to elbow. Keeping both hands in front of your stomach helps you to be aware of breathing.

During kinhin, a special hand position is called “shashu”. Put your left thumb in your left hand, fingers around it and place it under your breastbone against your body, close your right hand around it so that the bottom of your arms forms a horizontal line. There are various variations on this in the various zen schools. However, the horizontal line always remains the starting point. We walk in a row. There is no talking. You walk as upright as you can, the posture of the upper body as with zazen, the shoulders low and relaxed. Kinhin is trying to walk in such a way that you feel how your feet touch the ground, how your body moves through space, how breathing and walking have the same source of movement.

During this kinhin the eyes are fully opened but you keep your eyes on the front. You don’t look around at the environment. The attention is mainly focused on the inside.

The walking pace is low, you make the steps in a somewhat delayed way.

In this very slow form you usually walk in an individual line. If you walk in circles in the meditation room, the gaze of all the runners except the first is focused on the back and shoulders of the previous runner.

Fast kinhin

The fast kinhin is like the slow one with only a difference in walking pace. In most groups, you alternate the slow and fast by a sign from the one who leads. Every zazen period (usually 25 minutes) is alternated with a walking meditation of approximately 10 minutes.

In the introductory course we learn the slow and fast form as a combination.